When Mindfulness Training Doesn't Work

Tuesday, April 22, 2014 at 05:45PM

Tuesday, April 22, 2014 at 05:45PM By Jonathan S. Kaplan, Ph.D.

This article appeared in a professional newsletter a couple months ago. I though that it might also be interesting to other folks, too. JSK

Interest in mindfulness--observing and allowing thoughts, feelings, sensations, and perceptions as manifest moment-to-moment (Kaplan, 2010)--has exploded over the past 3 decades. From its integration into formal psychotherapies to neuroimaging studies of its effects on the brain, mindfulness training has emerged as a significant healing approach. Yet, as clinicians, we sometimes hear from our patients that “mindfulness doesn’t work” for them. Indeed, in some instances, mindfulness practice seems to worsen a patient’s complaints. What’s going on here? In this article, I will share my own observations, based in incorporating mindfulness training into psychotherapy for the past 15 years.

The primary issue in the suitability of mindfulness training revolves around the fit between (1) the specific practice and (2) the intended purpose for (3) a particular person. Let’s examine each in turn:

Practice

Because mindfulness engenders a distinct way of relating to experience--any experience--there are a myriad of ways in which we can practice. Unfortunately however, our patients have tried just one practice (e.g., mindful breathing) and found it to be frustratingly difficult. At such times--just like we might pore over a thought record--we need to scrutinize the specific practice in order to determine the appropriateness of the technique. Sometimes, we find that the patient hasn’t been practicing mindfulness at all, but rather some assumption of what it is supposed to be (e.g., “not thinking”). At other times, when the patient has been practicing mindfulness correctly for a while, we might invite them to explore other pathways, such as observing physical sensations in a slow, deliberate way or thoughtfully savoring food or drink. While there is value in sticking with a practice persistently, we also need to be cognizant that our patients might abandon mindfulness training before it becomes helpful for them.

Purpose

Oftentimes, the main reason mindfulness training “doesn’t work” is that we have an agenda for what we “should” feel or experience. Despite the acceptance characteristic of mindfulness, we still resist unwanted experiences, like pain, sadness, shame, etc. We also hold a desire for improvement. We are wedded some idea of what we want or how we should feel, which is different from what we’re actually experiencing. Thus, we need to be quite careful with the motivation underlying practice. Admittedly, there has be some motivation or hope for an improvement in our condition, otherwise we wouldn’t practice at all. Yet, we need to hold this intention lightly and encourage our patients to do likewise. The essence of the practice is not goal-oriented. It is about surrendering to the products of our minds and hearts--not in ways that buy into the literal content, but rather the lived, experiential reality of what it’s like to be alive in this body at this time. Accordingly, with our patients, rather than presenting mindfulness training as a goal-directed enterprise, it is more beneficial to cultivate a sense of curiosity in the experience. Wondering what the practice will be like facilitates engagement, openness, and allowing.

Person

I have often met with people for whom mindfulness training is not appropriate, at least not yet. Some people have too much difficulty with perspective-taking, emotion regulation, impulsivity, or rumination, so mindfulness training is likely to be frustrating and even counter-productive. In such circumstances, it is necessary for the person to adopt a concentration-based practice prior to mindfulness training. That is, it is necessary to develop a certain steadiness of mind and heart through deliberate cultivation of attention. Brief meditations based on word repetition, visual perception, or visualization are a great places to start. The Relaxation Response (2000) provides a wonderful introduction to such meditations. In addition, physically based practices, like yoga or walking meditation, can provide better entryways than more subtle forms of mindfulness training (e.g., vipassana meditation).

In summary, it is important for us to consider the three P’s--purpose, practice, and person--when initiating mindfulness training with a particular patient. Such reflection will allow our patients better access to the healing capabilities of mindfulness and reduce any unnecessary frustrations or misunderstandings.

References

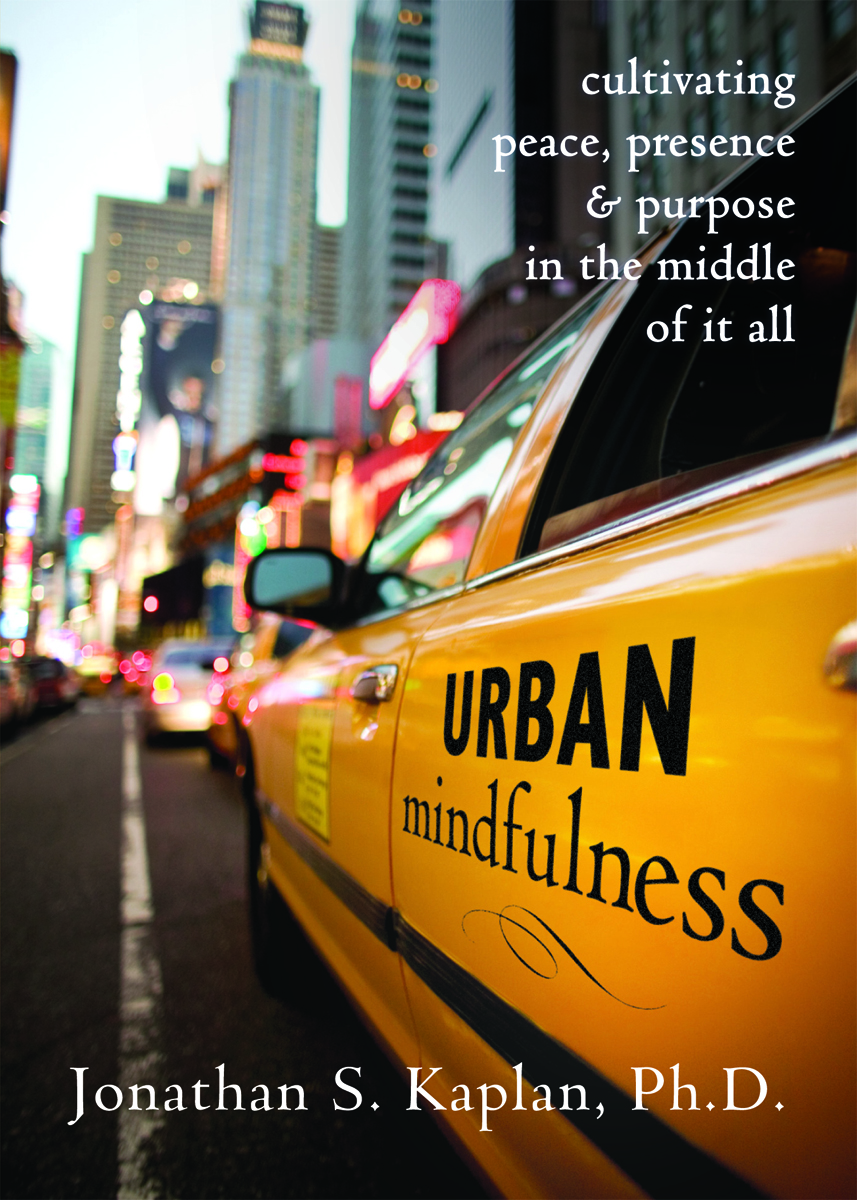

Kaplan, J. (2010) Urban Mindfulness: Cultivating Peace, Presence, and Purpose in the Middle of It All. New Harbinger: Oakland, CA.

Benson, H. & Klipper, Miriam (2000). The Relaxation Response. HarperTorch: New York, NY.

Reader Comments (9)

This is a great deal site. Totally is. Worth it.

I enjoyed reading your post and found it to be informative and exactly to the topic. Thank you for not rambling. Thanks.

Thank you for sharing such great things with us.

Amazing. Thanks for sharing. Watch New Zealand vs Sri Lanka World Cup 2015 live

Very motivated article, thank for the sharing. Cricket World Cup 2015 Predictions

Creatively written! You exposed the positive things of the topic and met the productive techniques

This is such a great article. It's important not to judge your experiences and it needs to be reiterated to beginners that it is called a "practice" for a reason.

Your post is unbelievably compelling and entertaining, A useful wording is a great way to highlight the significant aspects of the topic.

Amazon.com

Found this post really hit home with my struggles with meditation. I required a variety of techniques to build up a steadiness of mind and heart to effectively meditate. Also, like the part about it not being a goal oriented task. I had to come to a place of absolute acceptance in my practice, just experiencing the moment for what it is.